From Greenpeace Aotearoa educational resources.

The French government saw its nuclear testing programme as essential for France’s security (even though a nuclear armed world is hardly a secure one). But negative publicity about the testing would put pressure on the French government to stop its programme. It was for this reason that the French government wanted to stop the Rainbow Warrior’s upcoming anti-nuclear protest.

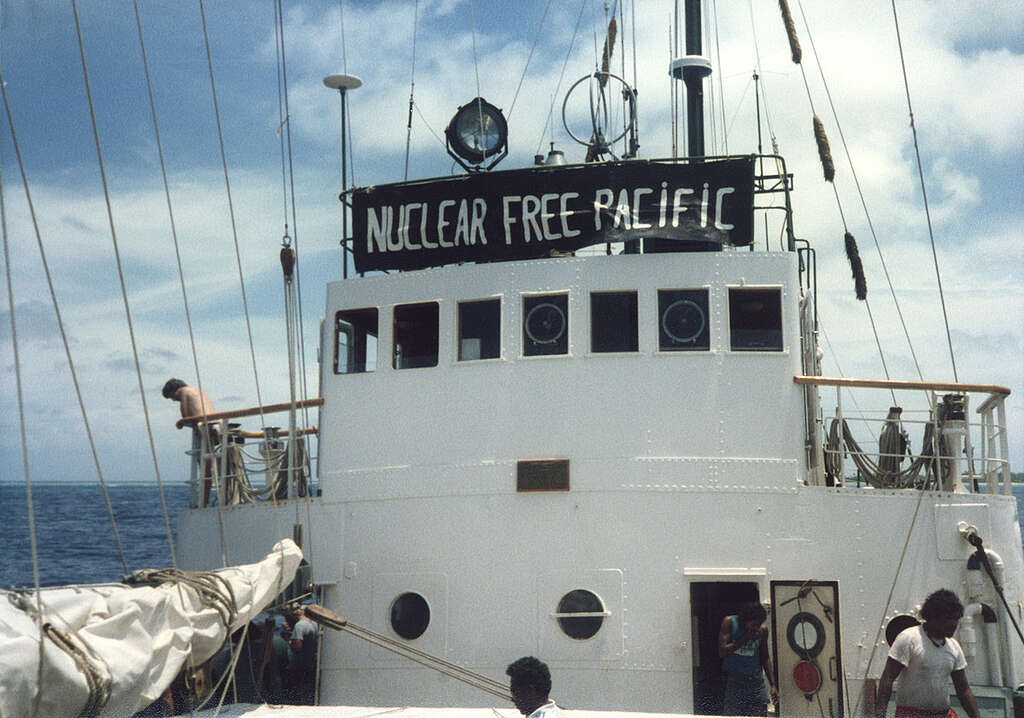

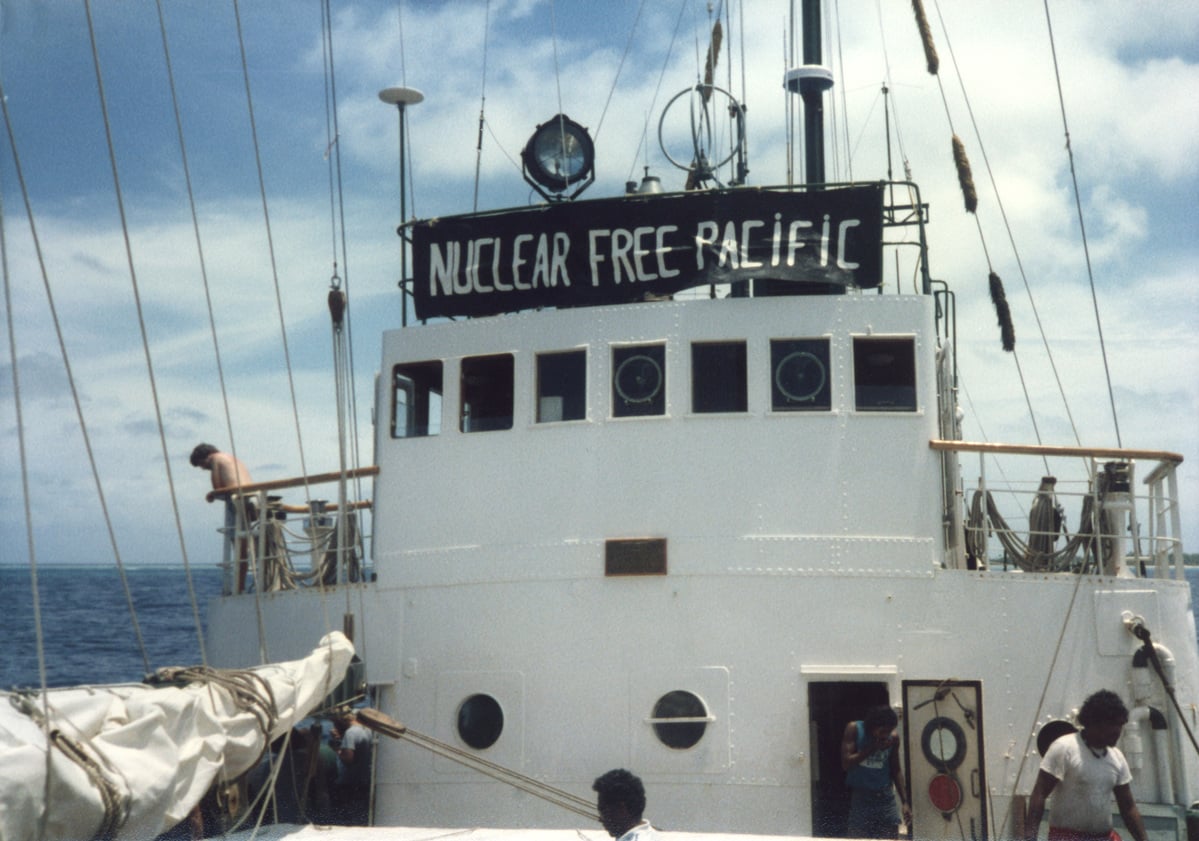

The Rainbow Warrior was a large vessel which could act as a flagship for the smaller protest yachts. French naval vessels would not be able to intimidate it as easily as the other, more fragile yachts. The Rainbow Warrior could carry large amounts of supplies, which meant that it could protest for a long period of time. The communications equipment on board would allow the crew to maintain radio contact with the outside world and send up-to-the-minute reports and photos to international news organisations.

The French navy would find it extremely difficult to deal with the non-violent tactics of the protest vessels. To avoid this, the French secret service DGSE was ordered to launch “Operation Satanique,” where French secret service agents were sent to New Zealand to sink the Rainbow Warrior before it could lead the protest flotilla.

At the time of the bombing, the Rainbow Warrior was about to lead a group of anti-nuclear testing vessels to Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia. To appreciate why the ship was bombed by the French government, it’s important to understand the political environment of the time, and how Greenpeace’s campaign against testing in the Pacific was so significant.

On 6 August 1945, the United States dropped a new and devastating weapon in the form of an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima in Japan. Three days later it dropped another atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki. The USA dropped these nuclear weapons to speed up the end of the war against Japan and avoid a costly ground invasion of the Japanese home islands.

But the world had never seen such powerful weapons of mass destruction. Each bomb was more powerful than 10,000 tons of TNT explosive. Entire sections of the cities were totally destroyed and tens of thousands of men, women and children were killed outright or in the days and weeks afterwards. These bombs released radioactive fallout which contaminated the environment. Many people would die later from exposure to radiation. Women gave birth to deformed babies. To this day, historians argue about whether or not such weapons should ever have been used against Japan.

After World War II, tension developed between the USA and the USSR. What became known as the Cold War (1945-1991) began, where the two superpowers and their allies competed to spread their different forms of government across the world.

The USA and the USSR competed to produce the most powerful nuclear weapons in order to ensure their security. Governments now knew that if they launched nuclear weapons at another nuclear power, they would most likely be destroyed by their opponent’s weapons.

The two sides very nearly started a nuclear war over the Cuban Missile Crisis. Given the fragile post-World War II climate, the nuclear powers became careful not to provoke each other.

The USA, Britain and France sought remote areas to develop their nuclear weapons. Up until the 1960s, atmospheric nuclear tests were carried out in the Pacific by these powers.

The USA used the Marshall Islands. The British used Christmas Island and the Australian outback. France moved its testing programme from Algeria to French Polynesia in 1966.

Nuclear devices were suspended by balloons high above the ground and detonated so that scientists could take measurements.

Atmospheric testing meant that radioactive fallout was carried by the wind for vast distances, which contaminated the environment. Significant numbers of people living on nearby islands like Rongelap in the Marshall Islands have since developed cancer. Women have had miscarriages and some have given birth to deformed babies (known as “jellyfish babies”).

From the late 1950s people in many countries became very concerned about the effects of nuclear testing on people and the environment. Many people in the Pacific argued that if the tests were safe, why did the nuclear powers not test in their own countries.

The USA and Britain stopped testing in the South Pacific in the early 1960s. Protest movements started up and the governments of Vanuatu, New Zealand, Australia and others called on France to stop testing at Moruroa Atoll. The French Government refused to stop tests and downplayed the risks.

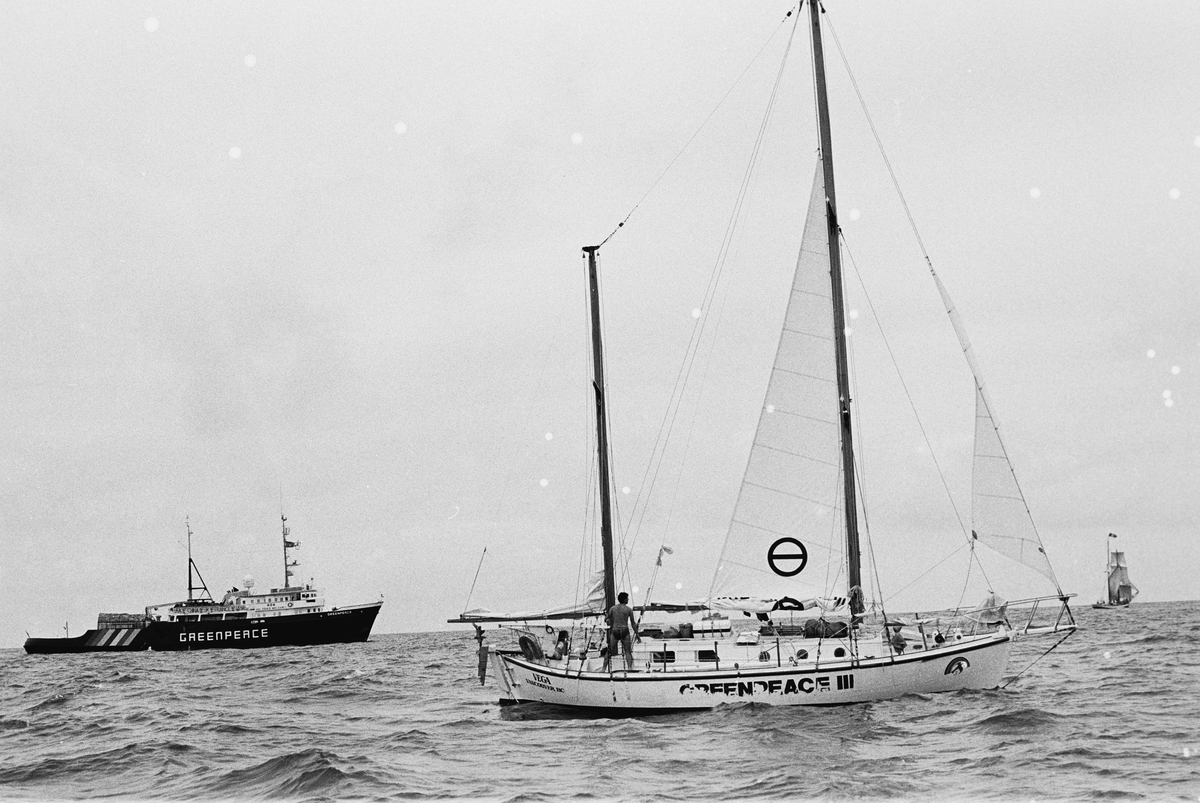

In June 1972, Greenpeace yacht Vega sailed into the forbidden zone outside Moruroa Atoll to stop the upcoming nuclear test by its presence. This was an extremely dangerous protest action, as the crew could be exposed to nuclear fallout from the explosion. David McTaggart (the skipper), Nigel Graham and Grant Davidson made blocks to seal the vents, to stop radioactive fallout entering the cabin. It was agreed that if they survived the nuclear blast and shockwave one crew member would expose himself on the deck to start the engine and motor out of the danger zone. After being ordered to leave, McTaggart refused to follow a French naval vessel out of the zone. This resulted in a chase where the Vega was rammed and McTaggart and crew were put in detention. Although the test went ahead, the Greenpeace action raised global awareness about the issue and put pressure on France to stop testing.

The New Zealand and Australian governments took France to the International Court of Justice in 1973 to try to stop the tests. However, France refused to follow the court’s ruling that it should stop testing. Norman Kirk, the New Zealand Prime Minister, sent two New Zealand navy frigates to protest on the edge of the Moruroa testing area.

A flotilla of civilian yachts were also protesting, including the Greenpeace yacht Vega skippered again by David McTaggart. Frustrated by McTaggart’s persistent non-violent protest actions, the French military boarded the Vega, where they severely beat McTaggart and one of his crew. He was hospitalised and lost vision in one of his eyes for several months. The French government tried to say his injuries were from a fall, but a crew member from the Vega smuggled out photos of the beating. This caused outrage in the international media and the French government was left humiliated.

Greenpeace was seen as a group of troublemakers by some members of the French government and military. The French navy found it very difficult to deal with non-violent protesters who would not cooperate. The protests led to the French abandoning atmospheric tests in favour of underground tests during 1974. However, protests at Moruroa continued in the hope that underground tests would also be stopped.

Read more about the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior

-

When was the Rainbow Warrior Bombed? A Timeline of Events

The Rainbow Warrior bombing took place on July 10, 1985, but it had been in the planning for months, and had repercussions that would last for years.

-

The investigation of the Rainbow Warrior bombing

On 11 July 1985, news spread of dramatic explosions on the Auckland waterfront. Greenpeace flagship the Rainbow Warrior had been sunk while moored at Marsden Wharf. One crew member, Fernando…

-

Why did the French bomb the Rainbow Warrior?

The French government saw its nuclear testing programme as essential for France’s security. But negative publicity about the testing would put pressure on the French government to stop its programme. It wanted to stop the Rainbow Warrior’s upcoming anti-nuclear protest.

-

Who was Fernando Pereira?

Fernando Pereira joined the crew of the Rainbow Warrior to bring his pictures of French nuclear testing to the world. A man who dedicated his life to peace. A determined photographer, a family man, a Rainbow Warrior – he will always be remembered.

-

Where is the Rainbow Warrior I now?

After the bombing, the Rainbow Warrior was given a final resting place at Matauri Bay, in New Zealand’s Cavalli Islands, where it has become a living reef, attracting marine life and recreational divers.