Australia is about to have one of the world’s biggest fishing vessels – from a fleet that has a track record of obliterating fish stocks around the world – enter its shores.

Blogpost by Karli Thomas, 01/02/2012

Rather than being afraid of the damage it will cause, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority has doubled the quota of mackerel, its intended catch – a fish already in a precarious state in the South Pacific. This ship is bad news – and it is not the first time we have said so.

Who is the Margiris?

When it comes to the fishing vessel Margiris there is only one word for it: PLUNDER. It was this word that Greenpeace activists painted on the side of the vessel when it was caught pillaging from the waters of Mauritania earlier this year and the word remains just as applicable as the ship makes its way around the globe with the intention of fishing off Tasmania, Australia.

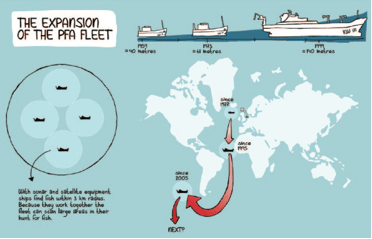

So who is she, this fishing vessel Margiris? She is an industrial super-trawler, and part of the fishing behemoth the European Association of pelagic freezer trawlers (PFA). This Association is responsible for some of the worst fishing excesses on the planet: giant factory trawlers vacuuming up fish from around the world, the largest of them a staggering 144 meters in length and with huge nets up to 600 metres long with openings reaching 200 by 100 metres in size.

A history of destruction

The PFA has its origin in Dutch companies fishing North Sea herring. When herring stocks collapsed and the fishery was shut down in the region between 1977 and 1983, the companies began to hunt for new fishing grounds. Technological advances opened up new geographical possibilities. The vessels’ coolers were replaced with freezers, enabling them to stay at sea longer and fish in previously inaccessible waters and in 1995 these pelagic trawlers headed to the waters of West Africa to fish.

As recently as 2005, the PFA further expanded its territory into the south-east Pacific, fishing off the coast of Chile. At the time, fisheries in this region were unregulated, and what followed was wholesale oceanic plunder, recently exposed by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists: Over two decades, the South Pacific jack mackerel stock was reduced by a shocking 90%.

The next target: Australia

As these massive super-trawlers drive one fishery after another to its knees, they desperately search for new fishing grounds. It appears that Australia may have provided part of the answer to the question “where are they off to next?” posed by Greenpeace earlier this year in Ocean Inquirer. This week, media reports have revealed plans for the Margiris to fish for mackerel and redbait off Tasmania. And it seems her way there may have been paved with a recent doubling in the mackerel quota by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority – a group that includes a representative from Seafish Tasmania, the company planning to bring Margiris to fish in Australia.

Where to plunder next? For at least one of the PFA super-trawlers, the answer appears to be: Australia.

Perhaps not the most sensible move when you consider that mackerel is a crucial species low in the food chain and important in the diet of larger fish like bluefin tuna (stealing their dinner just adds insult to injury: Southern bluefin is already listed as critically endangered).

The solution

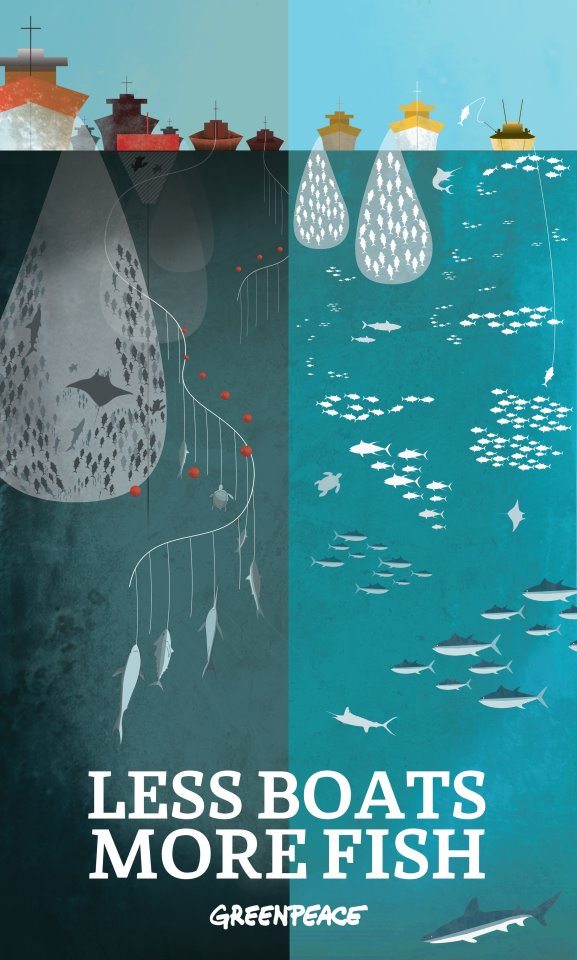

The best things we can do for our oceans right now is to cut the bloated global fishing fleet back to a size that fits a sustainable global fishery – keeping the best low-impact fisheries that contribute most to coastal communities – and set aside 40% of our oceans in a global network of marine reserves which will allow marine ecosystems to recover. The latter requires an oceans biodiversity agreement which conservation-minded governments are pushing for at the United Nations and Rio+20 conference.

The former requires a plan, but it’s not rocket science. We’ve got an estimated 2.5 times over-sized fishing fleet, so more than half must go. How do you decide who goes? If it’s broken the law (and we’ve documented a fair few that have) – it goes. If it’s using a fishing method that leaves swathes of destruction or tonnes of bycatch in its wake – it goes. And if it’s so big that no stretch of ocean can sustain its hunger for fish – it goes. Goodbye driftnets, goodbye bottom trawling, goodbye fish aggregation devices and industrial super-trawlers, goodbye pirates. Hello pole and line fishing boats, FAD-free tuna seiners, hello local fishers taking their catch with sustainable gear. Welcome back, fish.