‘If it’s wrong to wreck the climate, it’s wrong to profit from that wreckage.’ (Bill McKibben, founder 350.org)

The Australian National University (ANU)’s decision to sell its shares in seven unethical resource companies has hit the headlines over the past week.

Suddenly ‘divestment’ is splashed across the front pages and the government is up in arms.

ANU’s decision comes off the back of some major wins, with councils, churches, superannuation funds and universities pulling their money out of dirty fossil fuels.

But in comparison to the trillions still invested, the divestment—while impressive—is pocketmoney. So why the fuss?

It’s not about the money

Divestment campaigns rely on investors pulling their money from unethical companies. This has led to the common misconception that fossil fuel divestment is all about finance. If enough investors divest from coal companies—so the thinking goes—then those companies won’t have enough funds to build new coal mines. But this is very rarely the case. Capital usually remains readily available: ANU’s investment in Santos, for example, will soon get picked up by another investor.

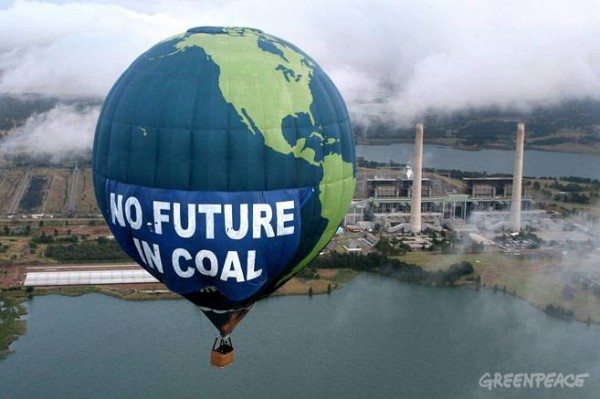

Instead, the divestment movement’s real power lies in its ability to stigmatise the fossil fuel industry and to draw attention to the huge contribution big coal, oil and gas make to the pollution that drives dangerous global warming. The recent widespread media coverage of ANU’s decision to sell a modest amount of shares is a great example: it has generated a huge amount of attention and debate about global warming and fossil fuel companies’ destruction of our climate.

Coal: the new tobacco

Once an industry is stigmatised in this way, it becomes much easier for governments to make decisions and pass laws which limit the harm it can cause. Think about the tobacco industry, which was a target of divestment campaigns in the 1980s and 1990s. Cigarettes are still legal but laws have ended tobacco advertising, brought in plain packaging, and banned smoking indoors and in public places—leading to a big drop in Australian smoking rates. Divestment can also be a powerful force to change ‘market norms’ around business lending—making it harder for fossil fuel companies to secure debt from banks to fund new operations. Several world-leading banks, for example, have committed not to lend money to mining projects along the Great Barrier Reef after public outcry over the damage they would cause.

Divestment campaigns have tended to follow a three step trajectory. Religious groups and industry-related public sector organisations usually divest first. Next, universities and some public institutions take action. The final step broadens divestment out to the wider market. The fossil fuel divestment movement is now at step two. Many religious organisations have divested and more and more academic institutions—like Stanford University in the US, Glasgow University in the UK and ANU in Australia—are doing the same. The more institutions that divest, the greater the stigma against harmful fossil fuels.

This is why the coal industry and its friends in government are up in arms. They know their history.

The backlash against divestment

The power of the divestment movement can be seen in the panicked reactions by the fossil fuel industry and their supporters to ANU’s divestment announcement. A minister in the Abbott government called the decision ‘a disgrace’ and has written to ANU’s Vice Chancellor to ask him to reconsider his principled decision. The Treasurer, Joe Hockey, has added his support, saying that the University was ‘removed from the reality’ of the Australian economy, while Prime Minister Tony Abbott has accused ANU of ‘unnecessary posturing.’ Earlier this year, the Minerals Council smeared fossil fuel divestment as ‘green imperialism at its worst’ and insinuated that it was against Australian law. The Australian Financial Review newspaper has recently run a campaign in its pages denigrating ANU and the divestment movement for daring to suggest that universities have a moral obligation not to profit from the destruction of our climate.

This kind of hysteria should remind us of the saying, variously attributed to Mohandas Gandhi and American trade unionist Nicholas Klein, about campaigns for social change:

‘First they ignore you. Then they ridicule you. Then they attack you. Then you win.’

We haven’t reached the end of that path yet, but the fossil fuel divestment movement has come a long way in a very short time.

You can help us get there by taking action today:

- Ask Sydney University’s Vice Chancellor, Michael Spence, to dump his University’s investment in Whitehaven Coal.

- Take part in Divestment Day on October 18th and put your bank on notice for funding destructive new coal mines.

- Send a message of support to the Vice Chancellor of ANU on their Facebook page.